Petra, Jordan

|

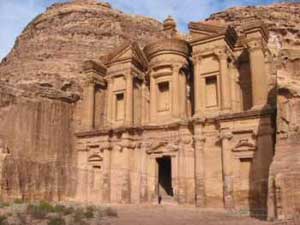

| Petra Treasury

(Al Khazneh) |

Petra ( rock in Greek) is an archaeological site

in Jordan, lying in a basin among the mountains which form

the eastern flank of Wadi Araba, the great valley running

from the Dead Sea to the Gulf of Aqaba. It is famous for having

many stone structures carved into the rock. The long-hidden

site was revealed to the Western world by the Swiss explorer

Johann Ludwig Burckhardt in 1812. Its famous description "a

rose-red city half as old as time" is the final line of a

sonnet by the minor Victorian poet John William Burgon, which

won the Newdigate Prize for poetry, given at Oxford, 1845.

Burgon had not actually visited Petra, which remained inaccessible

to all but the most intrepid Europeans, guided by local guides

with armed escorts, until after World War I.

Rekem is an ancient name for Petra and appears in

dead sea scrolls (4Q462 for example) associated with mount

Seir. Additionally, Eusebius and Jerome assert that Rekem

was the native name of Petra, apparently on the authority

of Josephus.

History

The descriptions of Strabo, Pliny the Elder, and

other writers identify Petra as the capital of the Nabataeans,

Arabic-speaking Semites, and the centre of their caravan trade.

Walled in by towering rocks and watered by a perennial stream,

Petra not only possessed the advantages of a fortress but

controlled the main commercial routes which passed through

it to Gaza in the west, to Bosra and Damascus in the north,

to Aqaba and Leuce Come on the Red Sea, and across the desert

to the Persian Gulf.

Recent excavations have demonstrated that it was

the ability of the Nabateans to control the water supply that

led to the rise of the desert city, in effect creating an

artificial oasis. The area is visited by flash floods and

archaeological evidence demonstrates the Nabateans controlled

these floods by the use of dams, cisterns and water conduits.

Thus, stored water could be employed even during prolonged

periods of drought, and the city prospered from its sale.

|

The end of the Siq |

Although in ancient times Petra might have been approached

from the south (via Saudi Arabia on a track leading around Jabal

Haroun, Aaron's Mountain, on across the plain of Petra), or

possibly from the high plateau to the north, most modern visitors

approach the ancient site from the east. The impressive eastern

entrance leads steeply down through a dark and narrow gorge

(in places only 3-4 metres wide) called the Siq (the shaft),

a natural geological feature formed from a deep split in the

sandstone rocks and serving as a waterway flowing into Wadi

Musa. At the end of the narrow gorge stands Petra's most elaborate

ruin, Al Khazneh ("the Treasury") hewn directly out of the sandstone

cliff.

|

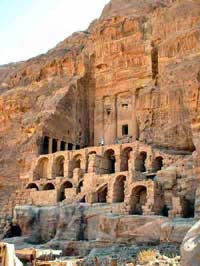

| Petra Amphitheatre |

A little farther from the Treasury, at the foot of

the mountain called en-Nejr is a massive theatre, so placed

as to bring the greatest number of tombs within view; and

at the point where the valley opens out into the plain the

site of the city is revealed with striking effect. Indeed,

the amphitheatre has actually been cut into the hillside and

into several of the tombs during its construction, rectangular

gaps in the seating are still visible. Almost enclosing it

on three sides are rose-coloured mountain walls, divided into

groups by deep fissures, and lined with tombs cut from the

rock in the form of towers.

It is thought that a position of such

natural strength must have been occupied early, but we have

no means of telling exactly when the history of Petra began.

The evidence seems to show that the city was of relatively late

foundation, though a sanctuary (see below) may have existed

there from very ancient times. This part of the country was

assigned by tradition to the Horites, i.e. probably cave-dwellers,

the predecessors of the Edomites (Genesis xiv. 6, xxxvi. 20-30;

Deut. ii. 12); the habits of the original natives may have influenced

the Nabataean custom of burying the dead and offering worship

in half-excavated caves. But that Petra itself is mentioned

in the Old Testament cannot be affirmed with certainty; for

though Petra is usually identified with Sela which also means

a rock, the Biblical references (Judges i. 36; Isaiah xvi. i,

xlii. 11; Obad. 3) are far from clear. 2 Kings xiv. 7 seems

to be more explicit; in the parallel passage, however, Sela

is understood to mean simply "the rock" (2 Chr. xxv. 12, see

LXX). Hence many authorities doubt whether any town named Sela

is mentioned in the Old Testament.

What, then, did the Semitic inhabitants

call their city? Eusebius and Jerome (Onom. sacr. 286, 71. 145,

9; 228, 55. 287, 94), apparently on the authority of Josephus

(Antiquities iv. 7, 1~ 4, 7), assert that Rekem was the native

name, and Rekem certainly appears in the dead sea scrolls as

a prominent Edom site most closely describing Petra. But in

the Aramaic versions Rekem is the name of Kadesh; Josephus may

have confused the two places. Sometimes the Aramaic versions

give the form Rekem-Geya, which recalls the name of the village

El-ji, south-east of Petra; the capital, however, would hardly

be defined by the name of a neighbouring village. The Semitic

name of the city, if it was not Sela, must remain unknown. The

passage in Diodorus Siculus (xix. 94-97) which describes the

expeditions which Antigonus sent against the Nabataeans in 312

BC is generally understood to throw some light upon the history

of Petra, though it must be admitted that the petra referred

to as a natural fortress and place of refuge cannot be a proper

name, and the description at any rate implies that the town

was not yet in existence. Brünnow thinks that "the rock" in

question was the sacred mountain en-Nejr (above); but Buhl suggests

a conspicuous height about 16 miles north of Petra, Shobak,

the Mont-royal of the Crusaders.

|

Monastery at Petra |

More satisfactory evidence of the date

at which the earliest Nabataean settlement began is to be obtained

from an examination of the tombs. Two types may be distinguished

broadly, the Nabataean and the Graeco-Roman. The Nabataean type

starts from the simple pylon-tomb with a door set in a tower

crowned by a parapet ornament, in imitation of the front of

a dwelling-house; then, after passing through various stages,

the full Nabataean type is reached, retaining all the native

features and at the same time exhibiting characteristics which

are partly Egyptian and partly Greek. Of this type there exist

close parallels in the tomb-towers at el-I~ejr [?] in north

Arabia, which bear long Nabataean inscriptions, and so supply

a date for the corresponding monuments at Petra. Then comes

a series of tombfronts which terminate in a semicircular arch,

a feature derived from north Syria, and finally the elaborate

façades, from which all trace of native style has vanished,

copied from the front of a Roman temple. The exact dates of

the stages in this development cannot be fixed, for strangely

enough few inscriptions of any length have been found at Petra,

perhaps because they have perished with the stucco or cement

which was used upon many of the buildings. We have, then, as

evidence for the earliest period, the simple pylon-tombs, which

belong to the pre-Hellenic age; how far back in this stage the

Nabataean settlement goes we do not know, but not farther than

the 6th century BC. A period follows in which the dominant civilization

combines Greek, Egyptian and Syrian elements, clearly pointing

to the age of the Ptolemies. Towards the close of the 2nd century

BC, when the Ptolemaic and Seleucid kingdoms were equally depressed,

the Nabataean kingdom came to the front; under Aretas III Philhellene,

(c.85 - 60 BC), the royal coins begin; at this time probably

the theatre was excavated, and Petra must have assumed the aspect

of a Hellenistic city. In the long and prosperous reign of Aretas

IV Philopatris, (9 BC - AD 40), the fine tombs of the el-I~ejr

[?] type may be dated, and perhaps also the great High-place.

Roman Rule

|

| Urn Tomb |

In 106, when Cornelius Palma was governor

of Syria, that part of Arabia under the rule of Petra was absorbed

into the Roman Empire as part of Arabia Petraea, and the native

dynasty came to an end. But the city continued to flourish.

A century later, in the time of Alexander Severus, when the

city was at the height of its splendour, the issue of coinage

comes to an end, and there is no more building of sumptuous

tombs, owing apparently to some sudden catastrophe, such as

an invasion by the neo-Persian power under the Sassanid dynasty.

Meanwhile as Palmyra (fl. 130 - 270) grew in importance and

attracted the Arabian trade away from Petra, the latter declined;

it seems, however, to have lingered on as a religious centre;

for we are told by Epiphanius of Cyprus (c.315 - 403) that in

his time a feast was held there on December 25 in honour of

the virgin Chaabou and her offspring Dusares.

Religion

The Nabataeans worshipped the Arab

gods and goddesses of the pre-Islamic times as well as few of

their deified kings. The most famous of these was Obodas I,

who was deified after his death. Du Sharrah was the main male

God accompanied by his feminine trinity; Al Uzza, Al Latt and

Mena. Many statues carved in the rock depict these gods & goddesses.

The Monastery, Petra's largest monument, dates from the first

century BC. It was dedicated to Obodas I and is believed to

be the symposium of Obodas the god. This information is inscibed

on the ruins of the Monastery (the name is the translation of

the Arabic "Ad-Deir").

Christianity found its way into Petra

in the 4th century CE, nearly 500 years after the establishment

of Petra as a trade center. Athanasius mentions a bishop of

Petra (Anhioch. 10) named Asterius. At least one of the tombs

(the "tomb with the urn"?) was used as a church; an inscription

in red paint records its consecration "in the time of the most

holy bishop Jason" (447). The Christianity of Petra, as of north

Arabia, was swept away by the Islamic conquest of 629 - 632.

During the First Crusade Petra was occupied by Baldwin I of

the Kingdom of Jerusalem and formed the second fief of the barony

of Kerak (in the Lordship of Oultrejordain) with the title Château

de la Valée de Moyse or Sela. It remained in the hands of the

Franks until 1189. Ruins of the Crusaders' citadel still stand

near the high-place on en-Nejr.

The first Byzantine church was discovered

by Kenneth Russell, an American archeologist, in 1991 with the

assistance of Dakihlallah, a Bedul Bedouin living in Petra.

Currently three churches have been excavated in Petra with the

assistance of the American Center of Oriental Research and the

Jordanian Department of Antiquities.

According to tradition, Petra is the

spot where Moses struck a rock with his staff, and water came

forth, and where Moses' sister, Miriam, is buried.

Decline

Petra's decline came rapidly under

Roman rule, in large part due to the revision of sea-based trade

routes. But in 363 an earthquake destroyed buildings and crippled

the vital water management system. The ruins of Petra were an

object of curiosity in the Middle Ages and were visited by the

Sultan Baibars of Egypt towards the close of the 13th century.

The first European to describe them was Johann Ludwig Burckhardt

in 1812.

Petra Today

• On December 6, 1985 Petra was

designated a World Heritage Site. A team of architects has been

(2006) set to work on a 'Visitor Centre', and Jordan's tourist

revenue is set to increase dramatically, with the mass production

of visitors on package holidays, although this is sensitive

to any hint of political instability. For example, the Jordan

Times reported in December 2006 that 59,000 people visited in

the two months October and November 2006, 25% fewer than the

same period in the previous year.

• John William

Burgon famously wrote that Petra was a "rose red city half as

old as time." Although at that time Burgon had never been to

Petra himself, the phrase has become strongly associated with

Petra. In fact the rocks of Petra are of many hues, few of which

could properly be described as "rose red".

Petra in movies and

popular culture

• David

Lean had planned to film lengthy scenes for Lawrence of Arabia

(1962) there, since T.E. Lawrence had investigated the site.

Because of budgetary limitations, however, the production pulled

out of Petra before the scenes could be shot.

• Petra

is featured in Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade as the Holy

Temple where the Holy Grail is located.

• Petra also appears

in many less distinguished films, and in popular fiction. The

site has also been used for television programmes and pop promotions.

• The independent film

Passion in the Desert used areas in Petra as a backdrop for

filming

Movies and T.V. series filmed in

Petra

• Son of God (2001) TV Series

• Terra X - Expedition ins Unbekannte" (1984) TV Series

• Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989)

• Mortal Kombat: Annihilation (1997) ...aka Mortal Kombat

2

• Mummy Returns, The (2001)

• Passion in the Desert (1997)

• Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger (1977) ...aka Sinbad

at the World's End

• Spiritual Warriors (2006)

• Xin A Li Ba Ba (1989)...aka A Li Ba Ba (1989) (USA:

video box title)

|